I was listening to the new song from John Mark McMillan (whom I'll call JMM from here on just for fun—or should I say, JM2?) and as his rough bass surged into my ears I began to get the sense of something—dare I say it?—sacramental.1

Better listen to it first (and check out this fabulously evocative lyric video):

The song (which definitely gives off some strong Coldplay vibes) opens with the rousing line: “The sun is leaning on the darkness again.” On its own, this doesn’t ring any sacramental bells especially, except for its figuration of the sun as a kind of Being in conflict with the darkness. (In other words, the sun is not just a sun: it’s a kind of person here. Yet its status as the sun also means that it’s much more than a person.) We’ll hold on to that thought momentarily, though, because the first verse is a doozy:

I saw images of God

Reflected out upon the deep

By prehistoric stars

Through millennia of grief

Hmm. So, if a sacrament is a visible sign of an invisible grace, we’ve got a lot to unpack here. JMM starts by pointing to the stars—these ancient material bodies, some of which are reflecting the activity from the very earliest moment of the cosmos—and he asserts that, reflected in them, are images of God. Like all signs, the referent here [i.e., the image of God] is at remove from the signifier that points to it [i.e., the star]. The star does not signify God Godself, but rather it is signifying an image of God. And, on top of that, JMM introduces this amazing idea that the gap between signifer and the signified reference, that asymptotal gap, is characterized by “millennia of grief.” The visible stars, whose twinkle occurred in a prehistoric time, point to a chain of images that ultimately point to God, yet the chain itself can be characterized only by this deep, unending, ontological grief.

Anytime the phrase “ontological grief” comes up, you’ve inevitably got to bring Matthew Arnold into the picture:

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Arnold’s classic Victorian poem, Dover Beach, emerges at exactly the moment where the consolations of religion have seemingly vanished in a matter of decades. Rather than a recent world, mere millenia in age and with a clear genealogy and history traceable back to the first man and woman, the discoveries of nineteenth-century geology, astronomy, and biology had suggested a much longer history. The thin veil separating the creature from its Creator thickened.

And so, the deep sadness of the universe, the discovery of which I believe is truly a gift of modernity, resonates along this gap between the referent and the signs all around us. Yet rather than simply sit in this smooth, comforting nihilism that is somehow also a humanism, I think JMM’s song is asking that we be delivered from this sadness—or at least delivered from a world where the darkness is all. Hence his reminder that the Sun is leaning on the darkness again.

The second half of the first verse takes Bruce Cockburn’s image of the Angel/Beast (from a song that JMM does seem to be in dialogue with) and puts JMM’s neologistic spin on it as the “excarnate beast.” If Jesus was "in-carnate," does this word imply (rather than relying upon a strict etymology) a going back to God while still remaining a beast? The speaker himself is this excarnate beast, feeling spiritless and haunted, perhaps listening to the “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar” of the Sea of Faith receding, yet at the same time stirred by “the ancient lights of heaven / Pressing down on me.”

I can’t go line by line through this, but there is so much food for thought.

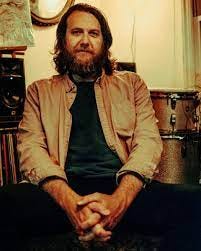

The second verse about “trading souls on the shores of Babylon” also cries out for a comparison with Bo Burnham’s 2021 show, Inside. (A more detailed comparison would of course have to begin with a comment on how much JMM looks like Bo Burnham). The verse also has some amazing insights into the impact of capitalism (i.e., Babylon) upon our evaluation of who we are. The way that this world minimizes individual souls to the point of making them easily exchangeable is then taken up in a later verse where JMM sings, “Every human creature is a galaxy of thought / You could spend your life on one / And it wouldn’t be for naught...” To treat a human—or the world—as anything less is to fail to “save the appearances,” as Owen Barfield would have it. It is a failure to recognize that there is an inner world beyond the surface.

To summarize, I think that the “sacramental” sense that I got from this song is grounded in that gap it attends to between the world as it appears (and how this is constantly under threat of becoming “disenchanted,” as JMM puts it) and the world it points to. And, as is the case with that sacramental orientation, which perceives the world through a lens of hope—with an expectation of God’s grace permeating all things—we believe that “the footsteps of the Midwife / are already in motion” so that our deliverance is not only a freeing from Babylon, but truly a birth, whereby the visible and the invisible become one.

A previous version of this was first posted on the Sacramental Ontology Society blog in June 2021.

Remember: a sacrament can be thought of as a visible sign of an invisible grace. So for something to be “sacramental” means that it is somehow performing this work of signing the invisible realm of God’s character.