Towards a Handmade Digital Artifact

How artists and designers are applying real world constraints to the digital in order to make something new

The Bubblewrap Proposition

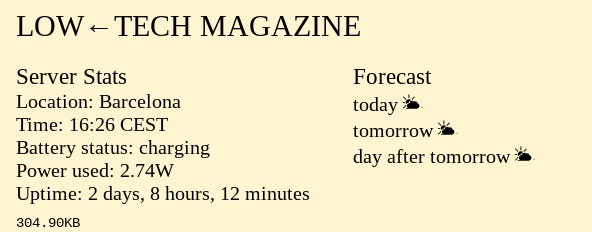

Bradley Hart creates art with bubblewrap, paint, and syringes.1 He starts by using a computer to transform an image — the Mona Lisa or a Van Gogh self-portrait — into a series of coloured dots. Once these dots and their colours have all been identified, he pre-fills a syringe with paint for each one. Working with a large sheet of bubblewrap, Hart then painstakingly moves from bubble to bubble, injecting a different colour of paint into each one. The results are beautiful, and there is something quite striking about what Hart calls “the bubblewrap proposition” that I feel resonates with the intent of this newsletter.

It’s a fascinating exercise: an attempt to create a handmade digital artifact. As he notes in his artist’s statement, the bubbles are meant to recall the 1 and 0 binary that defines the digital. But what is truly beautiful about the exercise is that it creates an effect that is only possible in analog, which is the “impression” canvas, where the paint that has been injected into each bubble spills out the back, pouring down the length of the picture and forming a thick layer of paint. The result is two images: one that shows the image translated pointillistically using the computer’s algorithm and another that results from the impression of the “hyper-inflated” or bursting bubbles streaking down the page like some kind of fantastic Francis Bacon painting.

Of course, this latter effect could be recreated digitally; however, what is unique is the serindipity and intense humanness encapsulated, if nothing else, in the relationship of the paint’s spill and the volume of paint the human artist injects into the bubble.

If we read the analog-digital relationship dialectically, then this handmade digital or computationally-facilitated analog artwork could represent as a third term, sublating (to use one translation of Hegel’s word, aufheben) the first two terms by preserving both their similarities and contradictions. The analog, negated by the digital, has been recovered in this third term once more — yet now with a difference.

Are there more examples of this kind of work?

Low-Tech Magazine

I think there’s something similar going on with the brilliant work happening at Low-Tech Magazine. From their unique use of solar power (described below) to the printed version of their website that they have available, Low-Tech Magazine is exploring the interface between the digital, which can often feel ethereal and unmoored from reality, and the analog, which encounters the constraints of such earthly obstacles as clouds blocking the sun. For this website, this constraint is literally a threat because the server for LTM is powered by a single solar panel in Barcelona. If the sun disappears for extended periods, the website can go down! The website is worth visiting if nothing else for the server stats it lists in the footer.

The decision to subject a digital object like a website so explicitly to the constraints of the real, analog — i.e., the given — world is inspiring. A website exists in an abstract realm. It’s light and movement. It’s text and image. We rarely know who wrote the content. We never know who designed the site. It lives in a portal on our laptop as far as we know or care. We forget that the site ultimately consists of actual pulsations of energy located physically within a server somewhere specific in the world. With LTM, though, many of these questions are raised anew — we are forced to remember the physicality of what is involved. It’s 4:26pm Barcelona time, and we’ve used 2.74 Watts of power.

The Open Book E-Reader

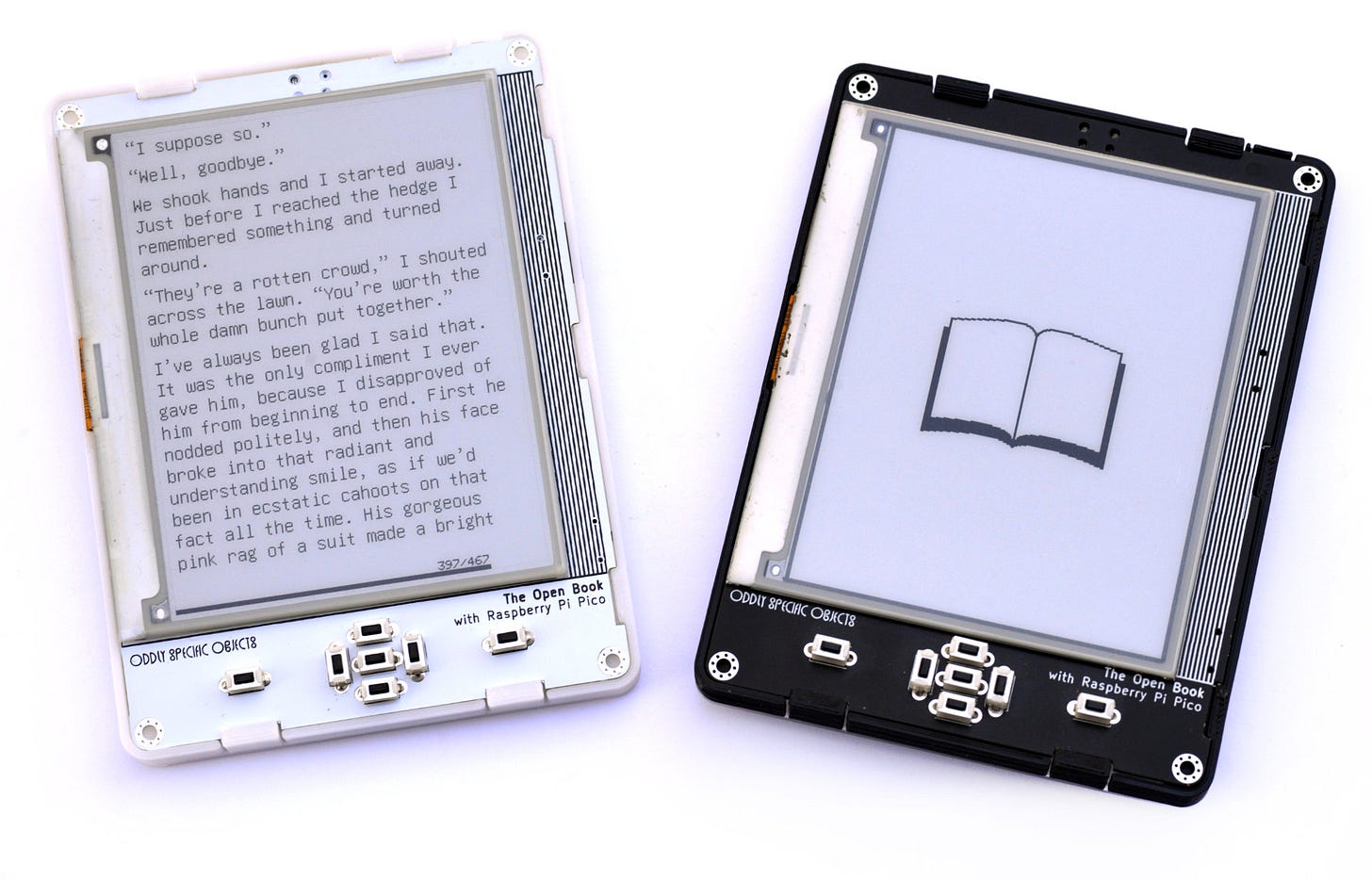

Another handmade digital object that I’ve been obsessed with for a while is Joey Castillo’s Open Book e-reader, which is intended to be an e-reader that one can build for oneself. Unlike the smooth, undisturbed surface of a Kindle, with its inscrutable interior, the Open Book is clunky, requires soldering, and will likely involve at least some formatting expertise if you are planning to upload any books.

Like the solar-powered website or the algorithmically-generated painting, the Open Book e-reader is an artifact that is both handmade and digital at the same time. It draws to the surface all of the constraints that “properly functioning” technological devices like Kindles or smartphones seek to obscure or redact. Yet it does not simply attempt to return to a pre-digital condition. Instead, it faces the digital condition head-on and seeks to reinterpret it. Castillo’s statement about the “Oddly Specific Objects” he creates (like the Open Book) resonates:

We live in an era of powerful but inscrutable gadgets: your smart phone arrives in your life fully formed, an object that is meant to be used, but not understood. […] Oddly Specific Objects aims to create devices that people can understand and in some cases even build themselves. The goal is to show that there is no magic to these gadgets.

I have suggested elsewhere that the real experience of magic requires that we in fact hold on to our disbelief rather than suspend it. Castillo is arguing for something similar. A gadget in which the operation is not at least partly understood can never be magical since the object’s rarity and inherent creativity can only be observed if that unbroken smoothness and perfect functionality is somehow interrupted. (And, of course, a great way to interrupt such smoothness is by being required to solder the object together yourself.) By showing that there is “no magic to these gadgets” through the involvement of users in the actual fabrication of the e-readers, a different kind of magic — one grounded in reality and the actual — becomes possible.

With this in mind, we can take all of these examples as challenging instances of a kind of performance art. The goal of this art is to alienate or, as one Russian critic put it, defamiliarize. Suddenly, in each of these examples, we are brought face to face with the digital, yet not in a manner we have seen it before. The digital condition we have become accustomed to — a radically simplified picture, a website, an e-book — take on a strange aspect, and we begin to ask questions like: What have we lost? What have we given up? Is another world possible?

At this point, at least, the next term in the dialectic is being prevented from arriving due to economic forces that continue to appear to make an ever more comprehensive digital condition the only option on the horizon. For handmade digital artifacts to begin to make an impact on our society, we may therefore need an equally handmade digital economy.2

I came across Hart’s work via Kottke.org, which is where Jason Kottke curates interesting links from across the Internet. Kottke got the link from Clive Thompson’s newsletter, which was citing a much more detailed article from Hyperallergic.

This sounds like I’m advocating for blockchain or crypto, which I can’t claim to be doing since I truly do not understand how any of that works, despite the best efforts of a good friend of mine to explain it. Instead, I’m trying to say — and may eventually have a chance to try at greater length — that there is a reason the digital is ubiquitous: global capitalism requires it. As long as the only way of living that we can imagine is one driven primarily by abstract flows of money, it is hard to believe any third term can yet arrive.